I’ve been working on whittling down my digital tsondoku. So this month has a random collection of things sitting on my ereader that I hadn’t gotten around to yet.

Cyberstorm by Matthew Mather

What happens when massive cyber attacks coincide with a devastating weather event?

Appreciated it wasn’t a survival story immediately about the good guys versus the bad guys. There was nuance and misunderstanding and desperation involved too.

The Cassandra Project by Jack McDevitt and Mike Resnick

A slowly-unfolding mystery of an international coverup about the Moon in the context of the Apollo missions.

A more gripping read than I think it had a right to be given its pace, but I think the drip of new information that drives the story along must have been about perfectly timed to keep me going.

Renegade by Joel Shepherd

This started out a bit stiff and clunky. Characters were a bit stereotypical. But it grew into itself fairly nicely and I was enjoying it by the end.

Space opera, power struggles, conspiracies, intrigue set at the end of a generations-long space war to earn humanity a seat at the galactic table.

The Old Willis Place by Mary Downing Hahn

The past two years or so each October I’d read aloud to the family A Night in the Lonesome October by Roger Zelazny. It’s a Halloween story told one day at a time throughout October.

This year the girls wanted something fresh and I found this billed for the right age range. It seems to have been a hit.

An abandoned manor house with a tragic history and the kids at the center of it all.

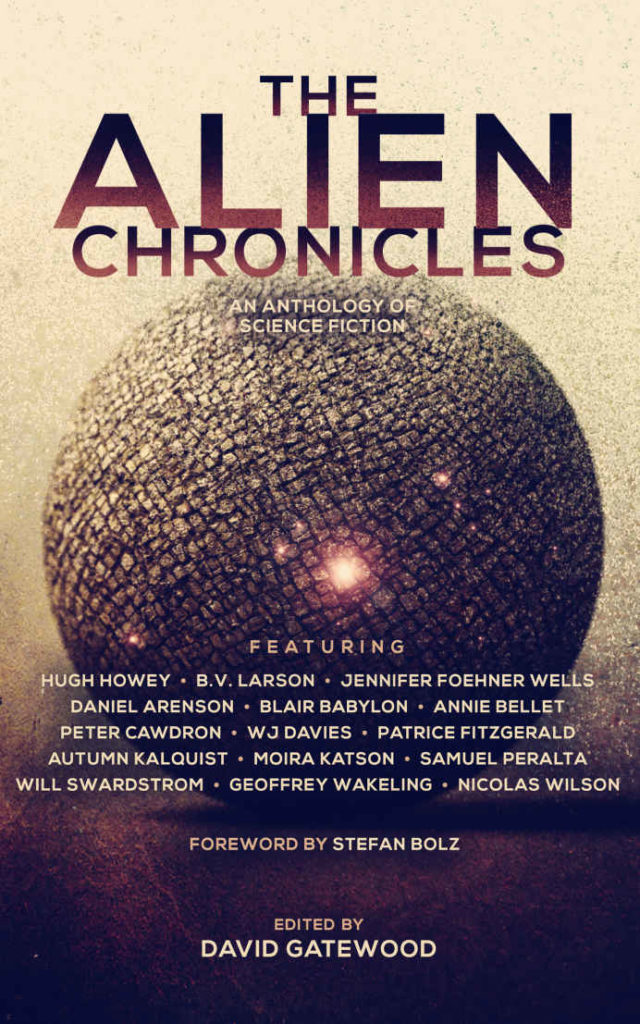

The Alien Chronicles edited by David Gatewood

Another anthology, this one nominally about human-alien interactions–often in the context of first contact.

Some decent stories in it, some that I found entirely forgettable and/or cliche.