Le Réveil des Dragons by Morgan Rice

An English fantasy book translated to French. A “chosen one” story about a girl who yearns to be a warrior and is destined for something greater.

An act of defiance against occupiers to save a dragon’s life condemns her kingdom to destruction. With nothing further to lose the kingdom fights for their survival.

When their destruction seems assured, the dragon returns and lays waste to their oppressors.

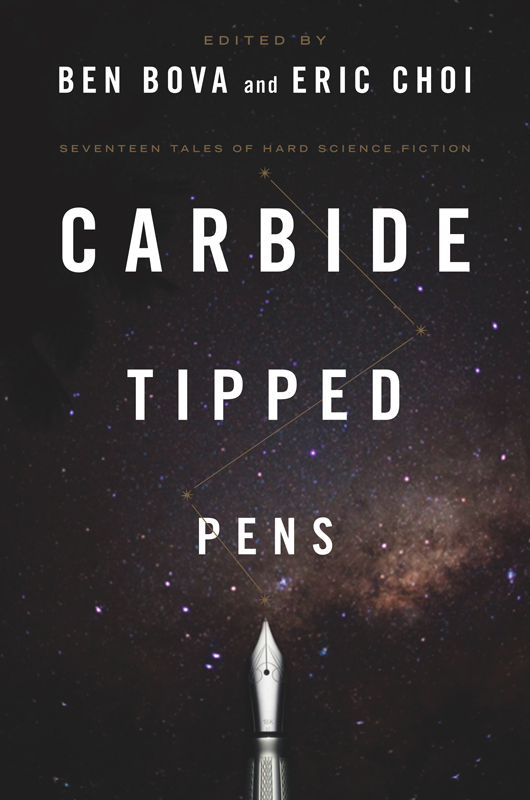

Carbide Tipped Pens a hard sci-fi anthology edited by Ben Bova and Eric Choi

A collection of 17 stories which I enjoyed–some more than others. None seem to have stuck out to me as being exceptional however.